During the 27th INFER conference, I had the chance to present a recent paper on the impact of climate vulnerability on fiscal risks. In this paper, we show for the first time that the political sub-dimension of religious tensions sharply magnifies this impact—doubling risk premia and ratings deterioration in vulnerable countries. More detail in the following blog.

The working paper is available on SSRN:

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4943355

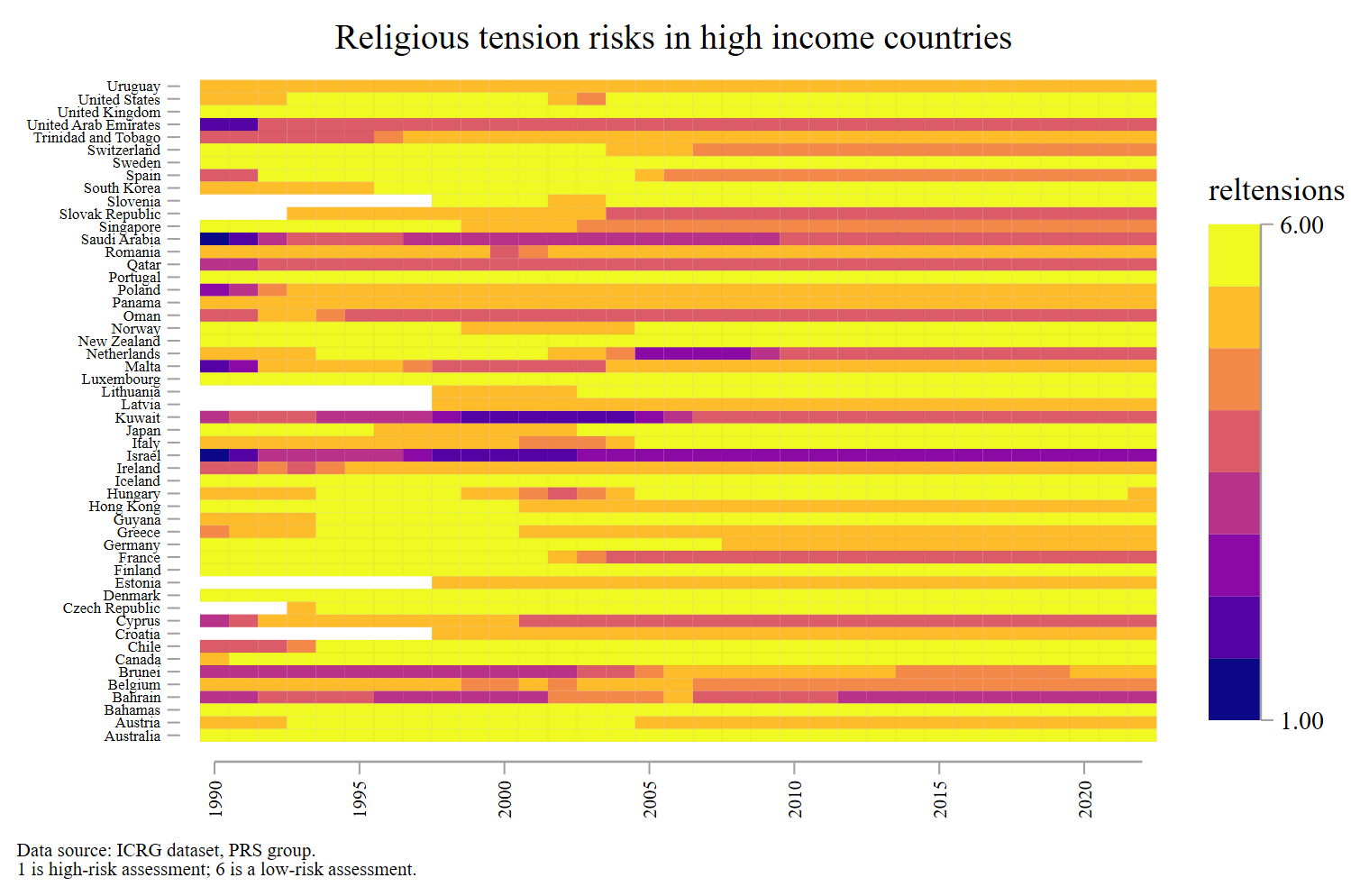

Hélène Rey asked a very interesting question on how the PRS group, which crafts the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) database, measures the religious tensions.

The methodology is an expert-based assessment — analysts evaluate the country on a predefined set of criteria related to religious tensions (e.g., degree of dominance, exclusion, suppression):

- A single religious group dominates society or governance or aspires to do so.

- Civil law is being replaced or undermined by religious law.

- Other religions are excluded from political or social processes.

- Religious freedom is suppressed, or expressions of religious identity are constrained.

Such tensions may spark civil dissent or even escalate to civil war.

I also argued that, even if religious tensions are not precisely estimated, the changes/turning points are based on real events, public policy debates and so on.

So, I asked ChatGPT (answer in italics) to evaluate this expert judgment dataset for the group of high income countries focusing on France and Netherlands, two countries that have faced some tensions since the start of the mid-2000s:

In France, religious tension risks increased gradually from the mid-2000s onward. The 2007 presidential campaign, with its heated debates on immigration and national identity, coincided with a visible shift. This was followed by legislative controversies over laïcité and religious symbols (headscarf, veil, burqa bans), which kept the issue alive. The sharpest spike appears in the mid-2010s, in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of 2015–2016 (Charlie Hebdo, Bataclan, Nice), which heightened polarization and brought security concerns to the forefront. While risks remain elevated, the pattern suggests a shift from episodic to more structural tensions after 2017.

In the Netherlands, by contrast, the turning point came earlier. Through the 1990s, the country appears in bright yellow, reflecting its image as a liberal and tolerant society. But the early 2000s mark a break: the rise of Pim Fortuyn, his assassination in 2002, and the murder of filmmaker Theo van Gogh in 2004 triggered a sustained debate over multiculturalism, integration, and Islam. From then on, religious tensions became embedded in the political landscape, amplified by the electoral strength of Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom (PVV). The indicator captures this rupture clearly: a sudden rise in the early 2000s, followed by persistently higher levels than before.

The main takeaway of this blog is, even if this measurement is surrounded by uncertainties, it replicates the main events and public policy discussions, allowing us to track time-series and cross-sectional evolutions.

Thanks for your attention. Comments and remarks are welcome. My other blogs on climate risk are susceptible to arousing your curiosity: https://www.jamelsaadaoui.com/tag/climate-risk