Today, I repost a blog written by Richard Baldwin on LinkedIn. The post is outstanding and gives multiple very interesting insights about current development on the economic consequences of recent geopolitical evolutions. I wish a good lecture.

The complete citation:

Richard Baldwin, International Institute for

Management Development, 22 November 2024, Factful Friday.

Introduction.

Why is geopolitics such a big deal these days? Is it just a passing fad? And why are geopolitics so complicated?

Today’s Factful Friday focuses on 3+3 facts that I believe suggest responses to these unanswerable questions. I’ll lay out the facts and then go all “Ian Bremmer” on you—he is my go-to guru on geopolitics. (Fun fact: I met him once in Mexico City in 2009. He was the headline floorshow; I was a sideline floorshow. Ian, if you’re reading this, don’t be a stranger. Drop me a line. No rush, I’m not holding my breath.)

Punchline before the joke.

I’ll argue that geopolitics, or more precisely, the economics of geopolitics, is in transition to an unknown destination. We are not heading toward a new cold war, nor will China become the new global superpower. In the view of Ian Bremmer, and yours truly FWIW, we’re heading toward something far messier. Today, and for the foreseeable future, some countries are superpowers in some domains. No country is a superpower in all domains. Worse yet for predictability, the set of key players varies by region and by domain. Ian calls this the G-Zero world.

Previously on the geopolitics show…

For those of you who have forgotten the previous episodes—or weren’t born yet—here is a quick recap of the first two seasons of the Geopolitics Show. I like to think of it as three games.

Back in the old days, during the Cold War, geopolitics was rather simple. It was a bit like playing the game of checkers. There were two players, the rules were pretty simple, and in fact, the game was so straightforward that almost every match ended in a draw. One group of countries stood behind the eastern player, the Soviets, while another supported the western player, led by the United States.

The main thing was that the rules were extremely clear. Everybody knew them. Almost everyone obeyed them. And above all, there was almost no interaction between the two blocks—no trade, investment, or movement of people. They were essentially two separate worlds that had their own rules, their own banking systems, their own supply chains, and their own economic philosophies.

The West believed in markets. The East believed in planning. For a complex set of reasons—one of which was that the market proved vastly more efficient and innovative than planning, especially as economies approached the frontiers of knowledge—the Eastern bloc collapsed. The USSR was buried along with Soviet-style planning.

Most amazingly, almost no one died when the Soviet Union called it quits and decided to ghost the 20th century. It collapsed under its own weight. Marx argued that capitalism contained contradictions that would eventually lead to its collapse and the triumph of socialism and communism. He was a big ideas guy, not details guy. He was right about the internal contradictions part, but not about that little detail about of which system had the contradictions.

That collapse moved us into the second phase of geopolitics, which I think of as “bingo”. One player called out the numbers, and everybody else sat in front of their Bingo Cards trying to do the best they could. Some people won, some people didn’t.

The main point, as far as geopolitics are concerned, was that the rules were clear. There were lots of people who did not like this game, but there was little they could do about it. The US dominated almost every sphere: economic, military, security, intelligence, cultural, financial—and let’s not forget the role of the dollar as the linchpin of the world financial system. While this was a legacy of the Cold War days, the dollar is and was like Facebook. Many people don’t like it that much, but they use it since everyone else they know uses it (at least people of a certain age). Technically, it’s called network externalities.

Checkers, then bingo. Oh, those were the days! At least, if you were attentive when choosing your parents’ passports. All that’s ended.

Now the game has become something akin to 3D Chess. But instead of two players as in the epic TV series, Star Trek, there’s about 150 players sitting around the table. Some of them play when the pieces are up on the top plane. Some play when the pieces are on the bottom plane. Some of them play all the time, and some of them never play. The rules are not clear, whatever rules there are a shifting, and in any case different rules apply in different regions and domains. (No, Star Trek was not a typo. I didn’t mean Star Wars, I meant Star Trek. If that’s new one on you, and you’re a SciFi fan, you are in for a treat. Bing-watch the original TV series. If nothing else, you’ll get to see what a young and svelte William Shatner looked like.)

3+3 facts that explain why this is happening now.

To my mind, there are three facts relevant to what changed in the US, and three facts that are relevant to what happened in China. And you can tell from the way I put that I believe today’s geopolitics is really a US-China thing at its core. That will hardly surprise anyone.

Now for the start-chart.

Western fact 1: G7 global economic clout diminished.

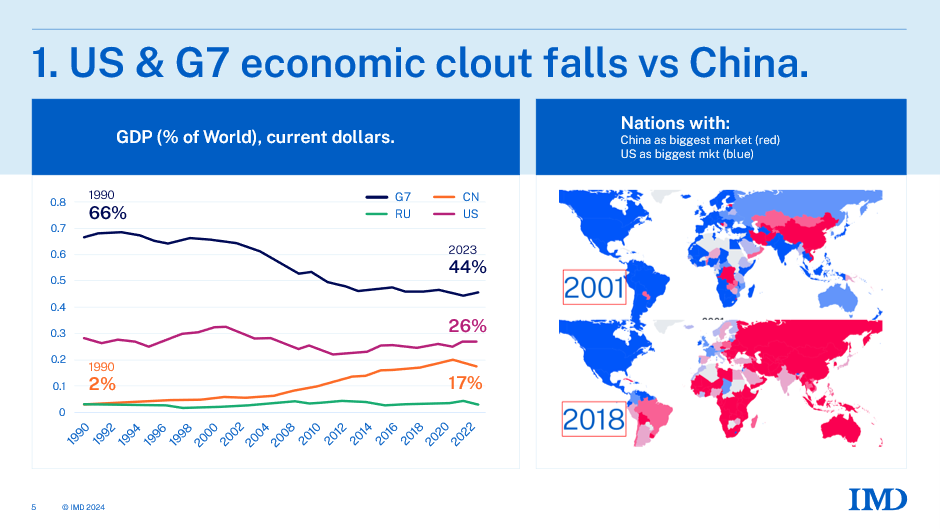

Back in 1990, the G7 industrialized countries–and they truly were industrialized back then–wielded enormous economic power, controlling about two-thirds of world GDP. This dominance extended across both supply and demand sides of the global economy. The United States of America stood as the clear leader of this influential group. When these seven economies made decisions, those decisions stuck–it was as simple as that. De facto, they maintained and enforced a rules-based trade system, controlled international organizations like the World Bank and IMF, and their central banks held sway over macroeconomic conditions worldwide.

Fast forward to 2022, and the G7’s share has plummeted to just 44%–a dramatic decline in dominance. Interestingly, the US share has held steady at around one-fourth of the world economy; it was the other G7 members whose GDP shares fell. Meanwhile, China’s share has experienced a miraculous rise from 2% to 17%. While impressive, this still isn’t enough for dominance. Even when China eventually surpasses the US economy in nominal terms, as projected, it won’t achieve the kind of dominance the G7 once enjoyed. Plus, China lacks something crucial–it doesn’t have a coalition of massive economies willing to follow its lead.

Looking at economic clout from another angle, we can see a telling shift in market influence. Back in 2001, more countries counted the United States as their largest market compared to China, as shown by the predominantly blue coloring in the top panel. But by 2018 (bottom panel), the picture had changed dramatically–there’s much more red and less blue, indicating China has become the dominant buyer for many nations. In the world of trade, where buying big gives you leverage, this shift reflects China’s waxing and America’s waning leverage. This new reality is something President Trump will have to reckon with if he tries to strong-arm countries by threatening to cut off access to the US market.

Western fact 2: US turns inward.

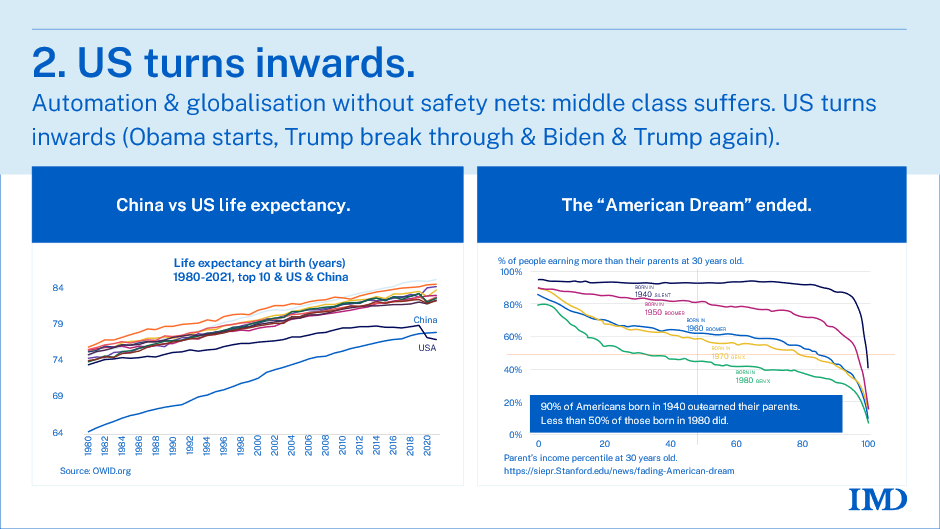

The next pair of charts looks at some symptoms of a disease that’s not as widely recognized as it should be, although candidate Trump surely understood it when he called the economy a disaster. The US badly managed the technology and globalization shock that affected all advanced economies in the 1990s and 2000s. And now the US middle class is backlashing. Politicians from the left and the right are telling them foreigners to blame, and they bought into the narrative. There is now a popular consensus that the US should focus on affairs at home. America should focus on “Making America Great Again”, and “America First”, to coin a phrase or two.

Below are couple of my favorite charts that illustrate the malaise facing America’s middle class, but I threw in a few more in the Annex in case these two don’t do it for you.

This middle-class backlash and its impact on US foreign policy didn’t start recently. It predates Trump significantly. Remember Obama’s first term when “trade” was treated like a four-letter word in Washington? While his predecessor, Bush Jr, never met a free trade agreement he didn’t like, Obama halted all trade negotiations (though he didn’t completely abandon the Trans-Pacific Partnership discussions). It was during this period that the US began undermining the WTO dispute settlement body–the first renewal rejection happened under Obama.

Trump didn’t start this trend; he simply mainstreamed that blaming of foreigners for America’s problems. Before Trump, corporate American didn’t really want to rock the boat with China since they were making so much money there and were afraid of subtle retaliation within China. Once Trump broke the omerta, there was not going back. By the time the Biden administration took office, the only realistic choice was to continue the China bashing but to do it with better table manners. Trump, as it turned out, was not an aberration but a culmination.

The evidence of American decline appears in stark statistics. US life expectancy has bucked the trend of other advanced economies and has recently fallen below China’s (this might be temporary and related to the mishandling of Covid in the US). But don’t think of life expectancy in an actuarial way. This isn’t just about living longer–life expectancy at birth serves as a comprehensive measure of a population’s well being, reflecting everything from healthcare and nutrition to community cohesion, income inequality, and education about lifestyle choices. What the chart tells us is that things went off track in the US that didn’t go off track in other advanced economies. This inference is support by a handful of charts in the Annex.

Perhaps even more telling than the early death of Americans is the death of the American Dream. Social mobility in America now lags behind many other advanced economies, including European nations. The data tells a striking story: while 90% of people born in the 1940s earned more than their parents by age 30 (particularly at median income levels), less than half of those born in the 1980s achieve the same milestone. A common modern narrative is that many Americans can’t even afford to buy the houses they grew up in, let alone achieve the traditional American Dream of buying something bigger and better. This frustrating reality has sparked considerable anger. Importantly, this wasn’t a sudden change but a gradual decline that began when President Reagan started dismantling the programs of the Great Society (Johnson) and the New Deal (FDR).

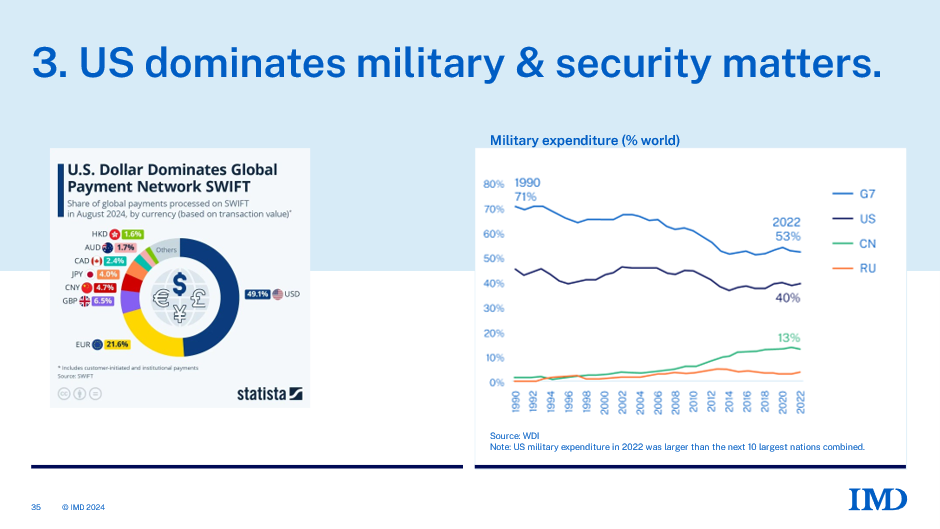

Western fact 3: US remains a military and financial superpower.

As many regular readers of Factful Friday already know, the United States maintains its superpower status in two crucial domains, as illustrated in our next chart. First, it continues to dominate global financial markets and banking. The dollar’s role as the world’s primary currency, in debt markets and in international trade invoicing gives America extraordinary leverage. Even more important is the central place of US banks in international payments and the US government’s weaponization of that dominance. For example, when the current administration decided to try to kill Chinese advanced semiconductor manufacturing, they used the dollar’s power to enforce their will on foreign firms.

Second, as shown in the right panel of our chart, America remains the dominant force in military spending. This combination of financial and military power, alongside its retreat from global economic leadership, creates a complex and puzzling situation in today’s geopolitical landscape.

This creates an intriguing complexity in today’s global power structure. Here we have a former global hegemon that still wields hegemonic power in the financial and military sphere yet has consciously stepped back from its role as an economic hegemon–or even leader of the G7–in the broader economic domain.

Eastern fact 1: China becomes sole manufacturing superpower.

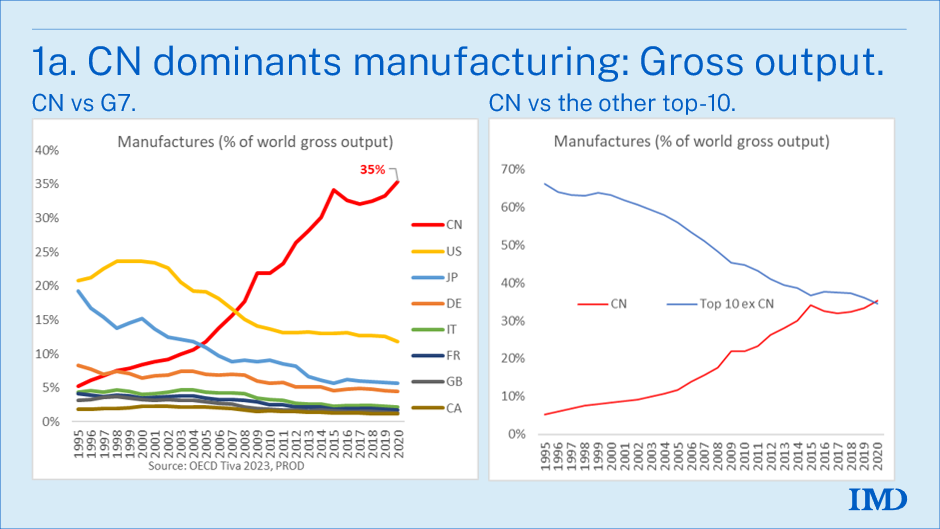

The first and most striking fact about China is its extraordinary dominance of global manufacturing—a reality that is not as widely recognized as it should be. The left panel of the chart below illustrates this dominance by plotting the gross output of manufacturing for China and the G7, each as a share of global manufacturing output. The red line, representing China, tells a remarkable story. Beginning at just 5% in 1995, it soared to an impressive 35% in 2020 (see the Annex for similar charts that look at China’s dominance measured in terms of manufacturing value added, exports, and jobs).

Even back in 1995, the sheer size of China’s population and economy meant its manufacturing share was already larger than most G7 countries, except the three major manufacturing powerhouses: Germany, Japan, and the United States. However, this began to change rapidly. China surpassed Germany in the late 1990s, Japan in the early 2000s, and the United States by the late 2000s. What’s even more striking is that since surpassing the US, China’s share of global manufacturing output has doubled again.

Two aspects of this transformation are particularly noteworthy. First, the speed of China’s ascent in global manufacturing is extraordinary. It happened so quickly that policymakers in G7 countries were largely caught off guard, failing to fully grasp the implications. Only in recent years has the enormity of this shift registered with Western governments. Only recently have they heard the “alarm clock.” While the G7 was repeatedly slapped the snooze button, China dominated global industrial supply chains.

This status is most clearly demonstrated in the right panel of the chart, which shows that China’s manufacturing share now exceeds the combined output of the next nine largest producers. These include the other G7 nations, along with South Korea and India.

While gross output is not the only metric for assessing China’s manufacturing dominance, its significance is undeniable. For those who prefer alternative measures such as value-added, trade flows, or employment, additional data is included in the annex. These metrics also reinforce the conclusion that China’s role in global manufacturing is unmatched and transformative.

Eastern fact 2: Chinese growth slows.

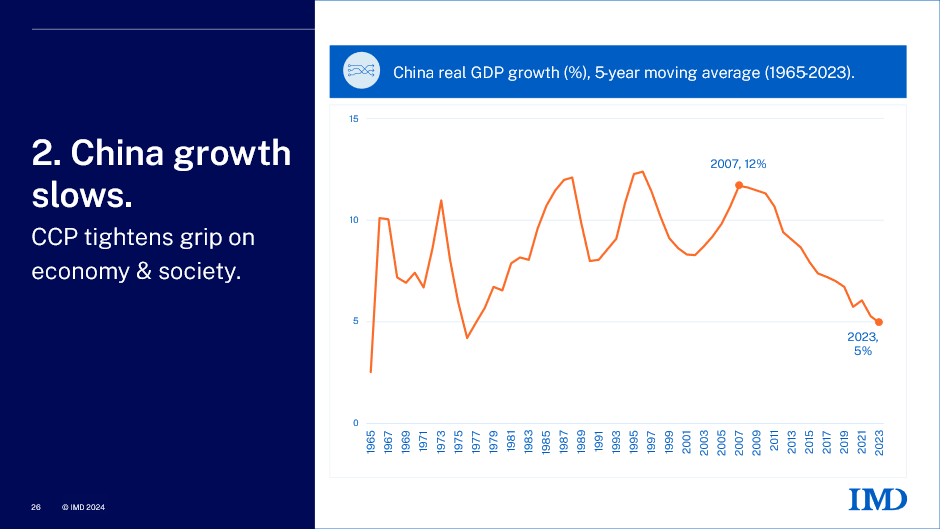

Another pivotal development reshaping geopolitics and bringing us to the current global dynamic is the significant slowdown in Chinese domestic growth. This shift is captured in the chart below, which plots the five-year moving average of China’s real GDP growth from the 1960s through 2023. For decades, Chinese growth was nothing short of miraculous. Following the death of Mao Zedong in the mid-1970s and the leadership transition to Deng Xiaoping, China experienced an economic boom that transformed its economy and society. During at least two decades of this period, average annual growth exceeded 10%.

At such a rapid rate of expansion, the income of an average Chinese worker would double more than five times over the course of a typical working life. This astonishing economic performance granted the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) immense legitimacy in the eyes of the Chinese population. The reasoning was simple: you didn’t need to believe in ideology to recognize that a government capable of engineering this kind of growth deserved the support of the people. Of course, the popularity of the Chinese government is based on other things as well.

However, since 2007, Chinese economic growth has decelerated markedly. Today, growth hovers around 5%, and many forecasts suggest it could remain at this level or even decline further. In Western economies, a consistent 5% growth rate would be cause for celebration and would almost certainly keep incumbents in power. But for a population accustomed to three or four decades of miraculous growth, 5% might seem underwhelming. While only a China expert could provide a definitive perspective, it seems the CCP still enjoys robust popular support. That said, the slowdown raises questions about how the party might sustain its legitimacy in an era of reduced economic dynamism.

This issue becomes even more pressing when viewed through the lens of historical precedent. A common narrative about the collapse of the Soviet Union posits that Soviet citizens were willing to support their government as long as living standards were rising, as they did during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. However, when growth stagnated, and the comparative success of Western economies became more evident, popular support for the regime waned. Could China face a similar challenge?

The second dimension of this second fact, which may or may not be related, is the CCP’s increasingly tight grip on both the economy and society. Through a series of measures widely reported in the Western press, the Chinese government has consolidated control over key sectors, imposed stricter regulations on businesses, and tightened social oversight.

By presenting these two developments side by side—China’s growth slowdown and the CCP’s increased control—it invites the question: Are these trends merely correlated, or is there a causal relationship? Is it a coincidence, or is it a strategic re-calibration aimed at maintaining stability in a slower-growth environment? Qui sais?

Eastern fact 3: the China dragon sheds its panda costume.

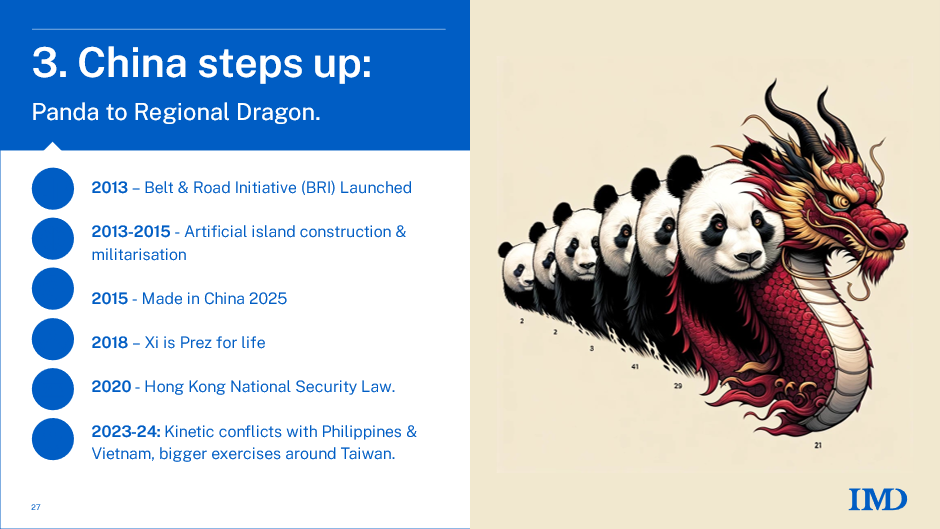

The final key fact from the East is the significant shift in China’s approach to the rest of the world. For most of the three decades of miraculous growth discussed earlier, China was a navel gazer—primarily focused inward. Its government dedicated itself to industrializing the country and improving the economic well-being of its citizens.

This inward focus began to change during the 2010s, as highlighted by the developments listed in the chart below. A pivotal moment in this transformation was the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013. This marked one of the first major instances of China turning its gaze outward in a structured and impactful way.

The BRI was all carrots and no sticks to start with. It was primarily about providing incentives, not imposing coercion. By offering substantial investments in infrastructure projects, it supported economic development in numerous developing countries. From building roads and ports to establishing rail networks and energy projects, the initiative aimed to create a more interconnected global economy. For many developing nations, this represented a significant opportunity, as China helped finance and construct the infrastructure necessary for their growth.

While the initiative has faced criticisms—most notably concerns about over-indebtedness and the long-term viability of some projects—it has largely been a win-win endeavor. Many participating countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America benefited from improved infrastructure that facilitated trade, investment, and integration into the global economy. At the same time, China bolstered its economic ties and influence, creating connections that linked developing nations more closely to its markets.

The BRI exemplifies how China’s priorities have evolved from an insular focus on domestic growth to a broader strategy of international engagement. This shift underscores a significant change in the global economic and geopolitical landscape, as China positions itself not only as a major economic powerhouse but also as a key partner and leader for many developing nations.

China’s outward focus took a more assertive turn in the 2010s, as it began to shift from economic engagement to military and territorial strategies. A symbolic step in this transformation was the construction and militarization of artificial islands in the South China Sea. According to the Chinese government, these islands fall within China’s territorial waters, but this claim is contested in international forums. In any case, the main point is that China’s claim overlaps with the territorial claims of several Southeast Asian nations, including Vietnam and the Philippines.

In 2018, another significant development occurred when the Chinese constitution was amended to remove presidential term limits, allowing President Xi Jinping to remain in office indefinitely. This change marked a notable consolidation of power and underscored a shift toward more centralized authority within China’s political system.

In 2020, the passing of the Hong Kong National Security Law added another layer to China’s increasingly assertive stance. While Hong Kong is part of China, this move undermined the “one country, two systems” framework, which many believed would preserve Hong Kong’s distinct political and legal autonomy.

More recently, kinetic actions involving the Chinese Coast Guard and vessels from neighboring countries have further heightened tensions. These incidents are looking a lot more martial than, say, building ports and railroads under the BRI. Historically, China’s approach to asserting these claims was more restrained, more panda-like. In recent years, they are more dragon-like.

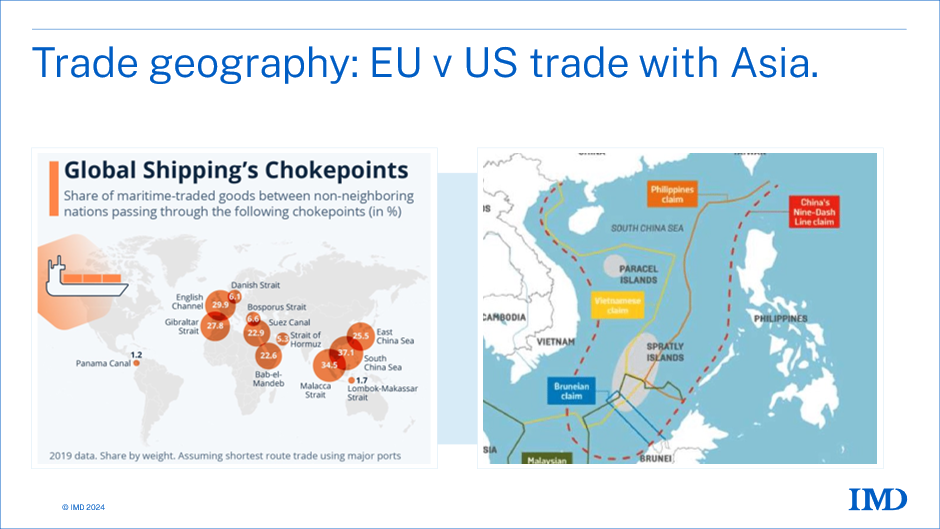

These disputes in the South China Sea are not just a regional issue—they hold global significance, particularly for Europe. Most of Europe’s sea-born trade with East Asia passes through these waters. This turns regional conflict in the South China Sea into a matter of strategic importance for Europe.

3+3 facts and today’s confused geopolitics.

Now we come to the part where I channel my inner Bremmer. By the way, you really should watch his explanation of today’s confused geopolitical situation and how we got here. Watch the first nine minutes of this TED talk. After minute nine, he starts on a trajectory that seems to be taking him towards a Omni Consumer Products outcome (have you seen RoboCop?).

Be forewarned that I don’t have a license to draw the lines connecting the 3+3 data-dots I laid out above, and geopolitics. I’m an international economist, not an international relations scholar, but some of you may be used to it. I’ve been coloring outside the lines ever since my first book for general readers, The Great Convergence in 2016. Proceed with caution: management assumes no liability for any harm or inconvenience arising from your choice to continue reading.

Connecting the data-dot to today’s geopolitical situation.

The first step in the shift from bingo to 3D chess was the dramatic decline in the G7’s economic clout in global affairs, followed by the US stepping back from leading this diminished bloc. Quite simply there is no hegemon in the global economy. The US accounts for about 26% of global GDP, China 19%, the EU 16%, and Japan just 4%. No economic power dominates the world the way the G7 did as recently as the 2000s. If the US were interested in knitting together a coalition of like-minded, advanced economies, it might be able to restore hegemony in the economic sphere. But its middle-class backlash means it won’t.

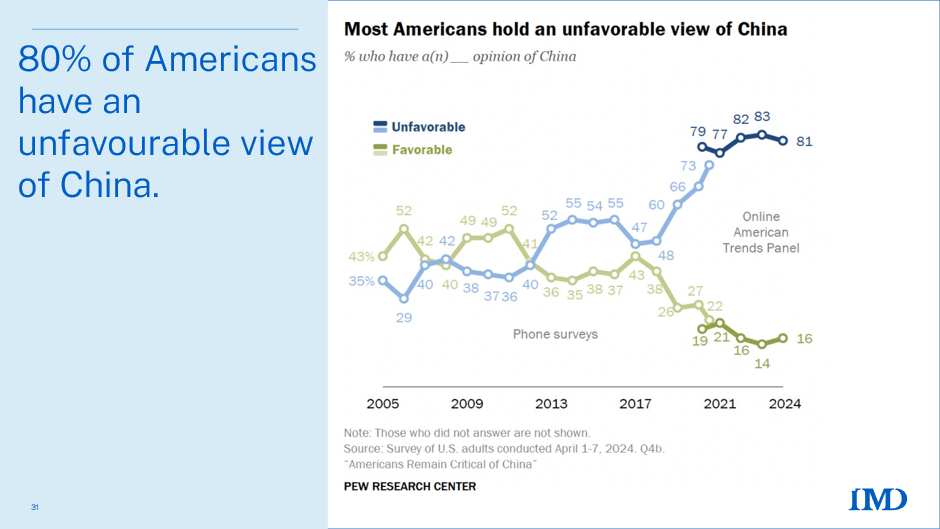

There’s a widely held belief among US voters that foreigners are to blame for much of their struggles. I think this is a misdiagnosis, but as my cross-country coach in Wisconsin used to say when I was in high school, “thems is the facts.” Blaming foreigners, especially China, is actively encouraged by many US influencers of all stripes. The chart below shows that most voters are listening to them; 80% have unfavorable views of China.

In a word, the US shifted from trying to make the world safe for American business—and, by extension, the business of other nations—to turning inward. Both the Trump and Biden administrations have made it pretty clear that it’s not their job to help American companies do business abroad. And this isn’t a new development. The last new trade agreement the US signed was with Korea in 2007. The deal with Canada and Mexico was revised under Trump, but that reduced rather than enhanced its pro-trade impact.

As the US stepped back from global economic leadership—and thus lost a key motive for maintaining the post-WWII global economic order—a power vacuum emerged. Regional players have stepped in. These players are now much larger, both economically and militarily, than they were twenty years ago when the US began stepping back from trade. From my reading of the press, these include Russia and Turkey in the Near East; Saudi Arabia, Israel, and Iran in the Middle East; and China in the Far East. Raise your hand if I missed someone.

And why is China stepping out of the panda costume? How does that tie into the facts? Allow me a sidebar on this one before answering.

Have you seen the 1997 movie Wag the Dog with Dustin Hoffman and Robert De Niro? In it, an unscrupulous US president, facing both a sex scandal and an election campaign, considers starting a war to distract voters and generate a ‘rally around the flag’ effect that he hopes will secure his re-election. Starting a war to turn eyes away from domestic woes is a time-honored ploy (knock knock, is Margret Thatcher there? Falklands. Falklands who? And do you remember Reagan invading Grenada when he was facing a challenging political situation at home?). But in the movie, there’s the twist: the President doesn’t want a real war. He wants a fake-news one. With help from a famous but equally unscrupulous Hollywood director, the electorate is treated to a fictitious war with Albania. There’s fake news footage, stirring patriotic songs, and heroic stories. I won’t spoil the ending for you. But let me ask—what would you guess? Was he re-elected?

The broader point is that governments whose popular support is waning can react in ways that rebuild that support on the back of conflict with foreigners. It’s above my pay grade to weigh in on whether slowing Chinese growth has anything to do with increased assertiveness of their territorial claims in the South China Sea. What do you think?

Summary and concluding remarks.

In my view, the 3+3 facts explain why most of the tensions are focused economics, manufactured goods in particular, and why they have come to a head now. They are related to the rise of China’s dominance in global manufacturing and industrial supply chains and America’s decision to step off the economic-leaders stage. To me, these are the core issues driving the new geopolitics. They are leading to good old-fashioned protectionism to shield national producers from China, as well as military and national security concerns, since most weapons are manufactured goods.

The messiness of it all stems from the absence of an overarching hegemon. China is the superpower in manufacturing. The US remains the superpower in all things financial and the unrivaled superpower in military capabilities—though it’s becoming increasingly reluctant to use those capabilities to make the world safe for business. This lack of cohesion—what Ian Bremmer calls the G-Zero world—means that many countries other than the US can exercise significant power within their own regions. We’re witnessing regional developments that likely never would have occurred when geopolitics resembled Bingo.

Concluding remarks and incautious conjectures.

When it comes to US-China tensions, Trump Tariffs: Season 2 will be bad but boring—same characters, same storyboard, but with much higher levels of protection leading to the same sort of managed trade deal we saw in Season 1. For Europe, however, things are likely to be far more dire. Europe is simultaneously at odds with both the US and China, which together account for about 38% of EU external trade. Moreover, Europe is far more dependent on the US security guarantee now than it was during Trump Season 1. Russia reminds Europe of this fact with each mention of tactical nuclear weapons.

Japan will probably get swept up in the turmoil, but many large emerging economies may actually benefit. With their main manufacturing competitors hobbled by tariffs in all the major export markets (G7, EU, and China), these emerging economies could seize new opportunities to industrialize.

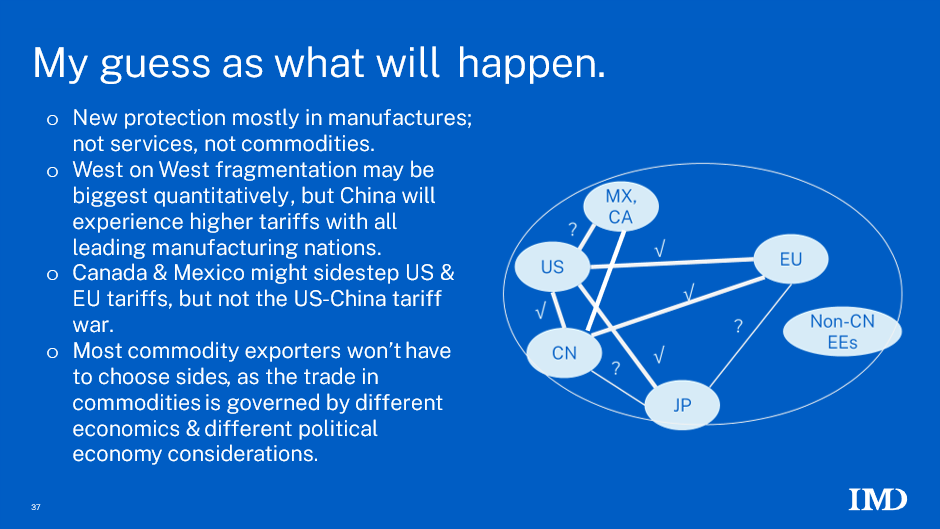

In a recent, online presentation that I gave at the Bank of Italy, I foolishly shared my predictions for Trump Season 2—and now I’ll foolishly share them with you. Here goes (the check marks indicate substantial two-way tariffs). BTW, no refunds if I’m wrong.

References.

Baldwin, Richard (2016). The Great Convergence: Information Technology and the New Globalization. Harvard University Press.

Bremmer, Ian (2023). “The next global superpower isn’t who you think”, TED Talk, https://www.ted.com/talks/ian_bremmer