In his recent article in Foreign Affairs, Nicholas Eberstadt explores the consequence of a world gone gray.

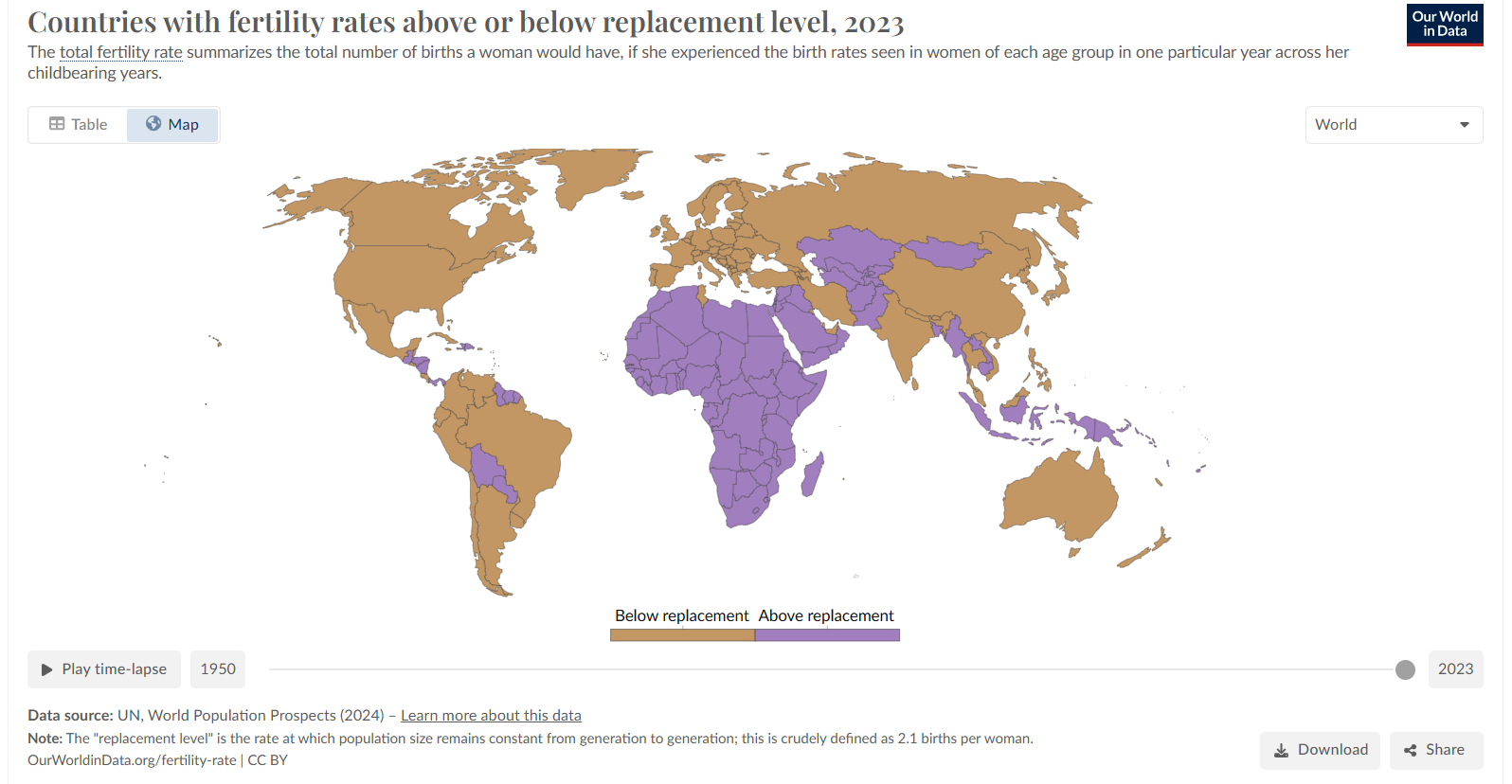

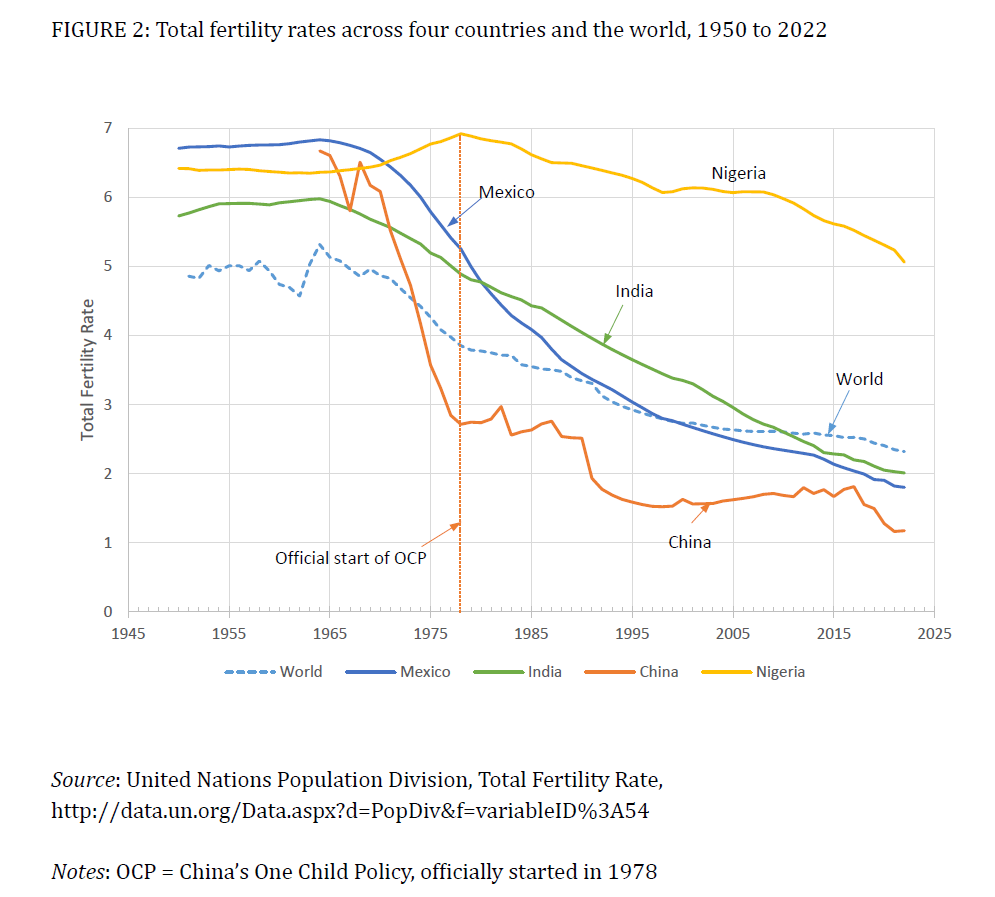

Most of the country in the world already have sub-replacement fertility rates. The consequences of this historical evolution constitute a major challenge for the world economy.

“Although few yet see it coming, humans are about to enter a new era of history,” writes the political economist Nicholas Eberstadt in a new essay from the upcoming issue of Foreign Affairs. “For the first time since the Black Death in the 1300s, the planetary population will decline. But whereas the last implosion was caused by a deadly disease borne by fleas, the coming one will be entirely due to choices made by people.”

Thanks to declining fertility rates, depopulation is all but inevitable—and leaders and citizens alike are unprepared for how this new demographic order will recast societies, economies, and power politics. But depopulation doesn’t have to be a death sentence for humanity, Eberstadt writes. “Rather, it is a difficult new context, one in which countries can still find ways to thrive.”

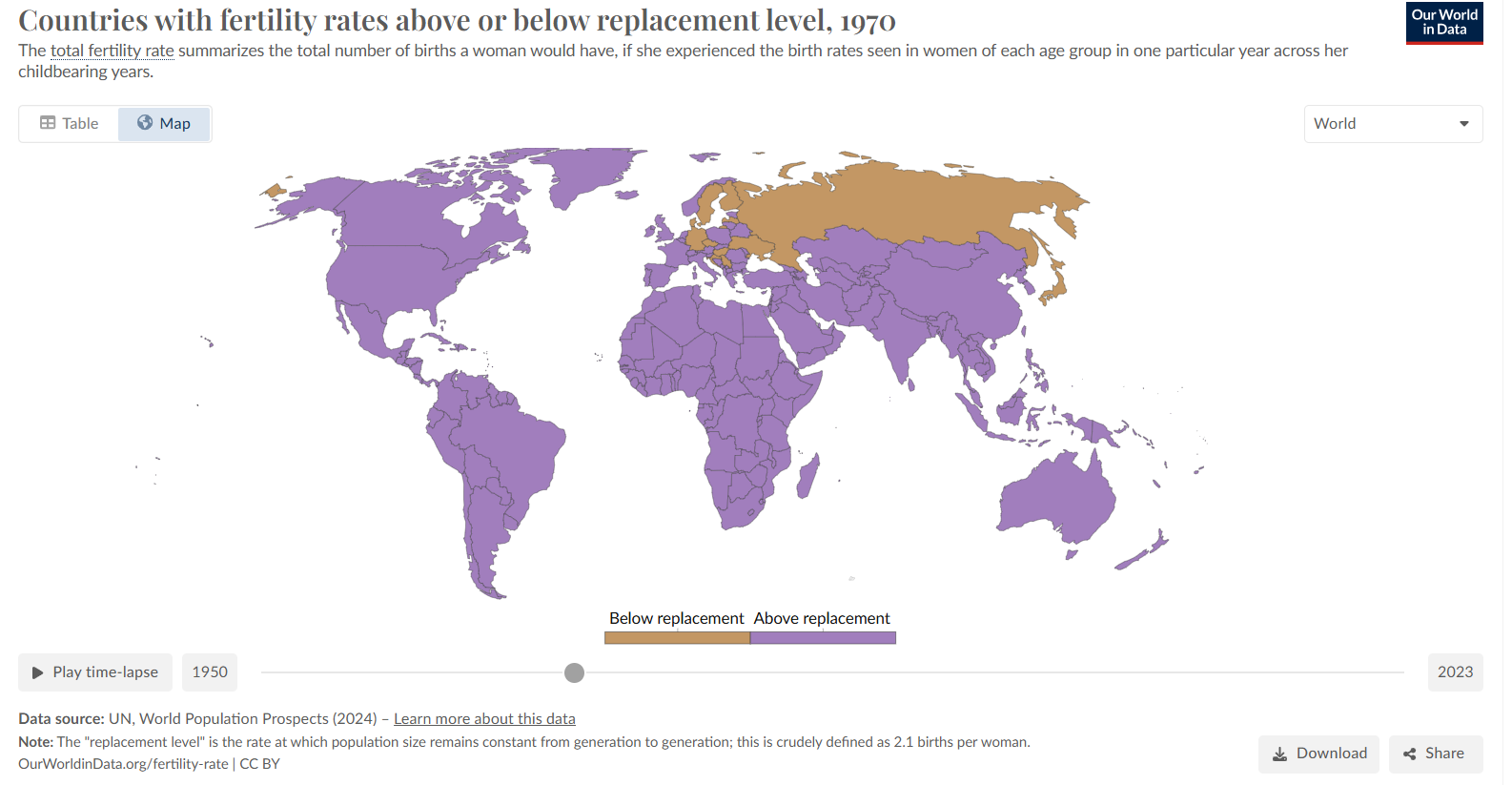

Our World in Data provides a very nice interactive visualization of this phenomenon. Below, I compare three point of time, 1950, 1970 and 2023:

Will the 2006 Alfonso Cuarón’s movie “Children of Men” become a reality? Probably not.

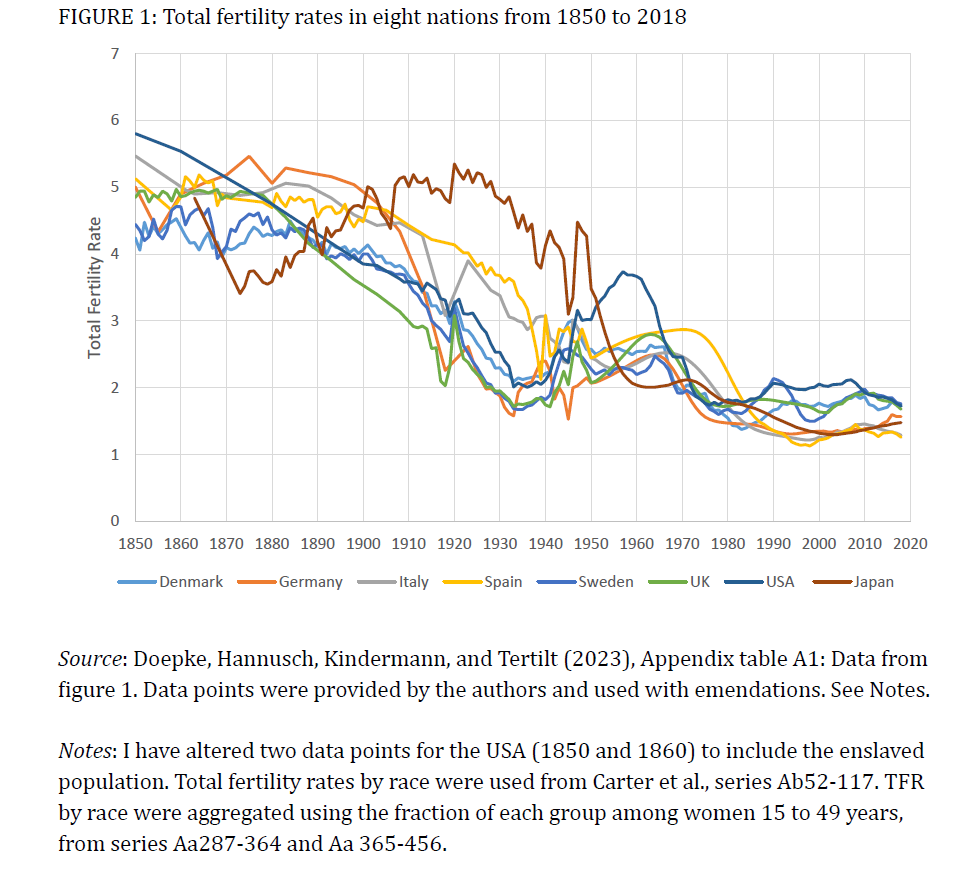

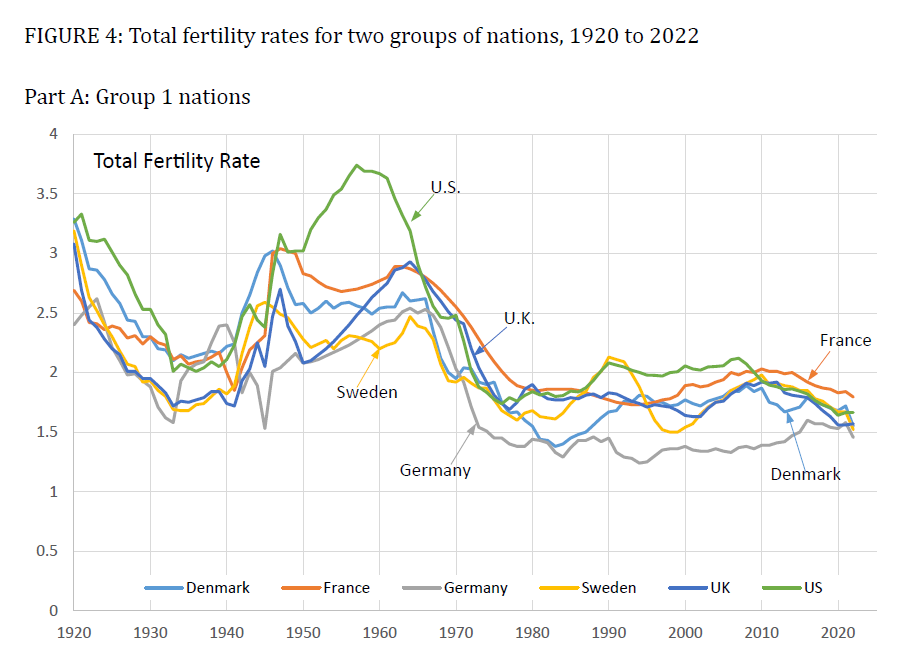

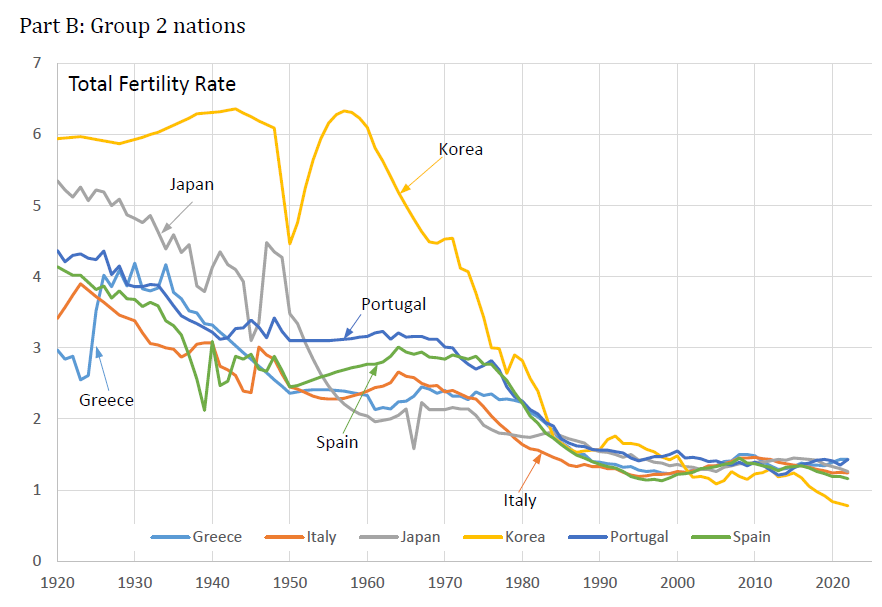

In her recent NBER working paper, Claudia Goldin explores the macroeconomic causes of these evolutions and provides long time-series data and asks the following questions:

“What are the forces that have led couples in some developed countries to have much lower fertility than in others, and why has fertility declined during particular periods?”

“I will draw on a revealing article that develops an implicit model about why a positive relationship between female employment and fertility might arise among richer nations (Feyrer, Sacerdote, and Stern 2008). That piece explored the notion that there is a U-shape (rather more like a backward J-shape) relationship between female employment, also sometimes income per capita, and fertility by country. Nations with low-income levels and low female employment have high fertility. With economic growth, female employment rises and fertility falls. But female employment may not increase as much in some nations and, interestingly, in those countries fertility will decline even more.”

She proposes a very pedagogical model, that reveals some insights:

“Decreased birth rates have been nearly ubiquitous around the world. But they aren’t always due to changes in contraceptive practices or legal constraints, and they aren’t always due to governmental policies that have tried to help working parents or encourage women to have more children. I have emphasized, instead, that decreased birth rates can be due to macroeconomic changes, especially those that impact differences across generations and thus that cause conflicts between the genders.”

“The model predicts that in periods of rapid and sudden economic and social change, men will want more children than women will want. The differences will be muted when economic change is slower and less sudden, but women will still want fewer children than will men. How can that change?

The reason for the difference, embedded in the simple model, is that women spend more time with their children, often by sacrificing their careers or by having lower incomes and thus becoming economically vulnerable. If they are divorced or separated, they and their children may suffer. They know this in advance and, in consequence, will resist having more children.”