An important problem in empirical macroeconomics is that geopolitics can influence economics in the long run. Relations between major powers evolve endogenously with trade, growth, financial conditions, and commodity prices, especially when one use low-frequency data (yearly data, for example). As soon as one regresses an economic outcome on a geopolitical index, we face the usual identification objections: reverse causality, omitted variables, and anticipation. The purpose of my recent work (Saadaoui, 2025) is not to deny these issues, but to build a causal scheme that is transparent about what variation is being used, why it is plausibly exogenous, and how the remaining identifying assumptions can be defended with evidence.

This post lays out a causal design based on geopolitical turning points, defined as surprise inflection points in bilateral relations. The central idea is simple: rather than treating geopolitics as a smooth process, we treat changes in the trajectory of relations—sudden accelerations and decelerations—as the relevant shocks. These turning points are operationalized using the second difference of a bilateral relations index, and then used as an instrument in a monthly local-projection framework.

1) The object of interest: short-run causal effects of bilateral relations

Let Pt* denote the latent state of bilateral political relations between China and a key partner (for example, the US). Markets and researchers only observe a proxy Pt, measured with error, but Pt* is the economically relevant object. In Saadaoui (2025), the empirical goal is to estimate the short-run dynamic response of an outcome Yt+h (oil prices are a natural example) to innovations in that relationship state.

Local projections are convenient here because they allow us to estimate horizon-specific impulse responses h=0,…,48 at monthly frequency, without imposing a tight parametric structure on dynamics. The key econometric issue is that Pt may be endogenous in the long run: economic shocks can affect relations, and relations can reflect many unobserved global forces that also affect Y.

2) First layer: turning points as a filter (why the first stage is strong)

The instrument is constructed as a turning point, operationalized as the second difference of the relationship index:

This transformation does more than “differentiate twice.” It acts as a filter that downweights smooth evolution and highlights inflection points—episodes where the relationship abruptly accelerates or decelerates relative to its recent path. In a geopolitical context, these inflections correspond to the moments when a relationship’s trajectory changes meaningfully: a deterioration suddenly intensifies, a crisis stops worsening, a rapprochement loses momentum, or a positive phase abruptly reverses.

This filter property is also what typically delivers a very strong first stage (see Saadaoui, 2025 for oil price dynamics; Saadaoui et al., 2026 for HS6 Chinese exports). Large values of Δ2Pt are not generic noise; they occur when the underlying diplomatic stance is being re-optimized or reoriented. Empirically, this tends to create an unusually tight link between Gt and the endogenous regressor Pt in the first stage. In other words, the instrument is not “weakly related” to the relationship state; it is mechanically designed to isolate precisely the variation that most strongly moves that state.

3) Second layer: non-anticipation (why turning points are challenging to forecast)

The most compelling feature of curvature-based instruments is informational. Economic agents may anticipate certain level changes or first differences in relations because some events are observable and scheduled: official visits, pre-announced policy meetings, staged summits, or even the gradual escalation of trade restrictions. Anticipation is possible because the news flow makes the direction of change partially predictable.

Turning points are different. The second difference captures changes in the change: it is not the announcement itself, but the unexpected shift in trajectory—whether a deterioration unexpectedly stops and stabilizes, whether improvement unexpectedly stalls, or whether tensions unexpectedly accelerate beyond what recent history would predict. At monthly frequency, there is rarely a reliable model or information—either for markets or for researchers—that can forecast such inflection points in a systematic way.

This logic can be turned into an empirical check using the data of Saadaoui (2025). A clean way is to run lead (no-anticipation) tests: replace Gt with a future turning point Gt+k (a 2-step lead is natural because the second difference uses 2 lags) and estimate reduced-form local projections of Yt+h on that lead, conditional on the baseline information set. If the instrument truly reflects unanticipated curvature innovations, future turning points should not predict today’s outcomes. When the estimated lead responses are statistically indistinguishable from 0 across horizons, this provides direct evidence consistent with non-anticipation: the turning point is not a predictable component already embedded in contemporaneous market dynamics. We obtain similar results for HS6 Chinese exports in Saadaoui et al. (2026).

4) Third layer: exclusion restriction (what it means, and what would be required to violate it)

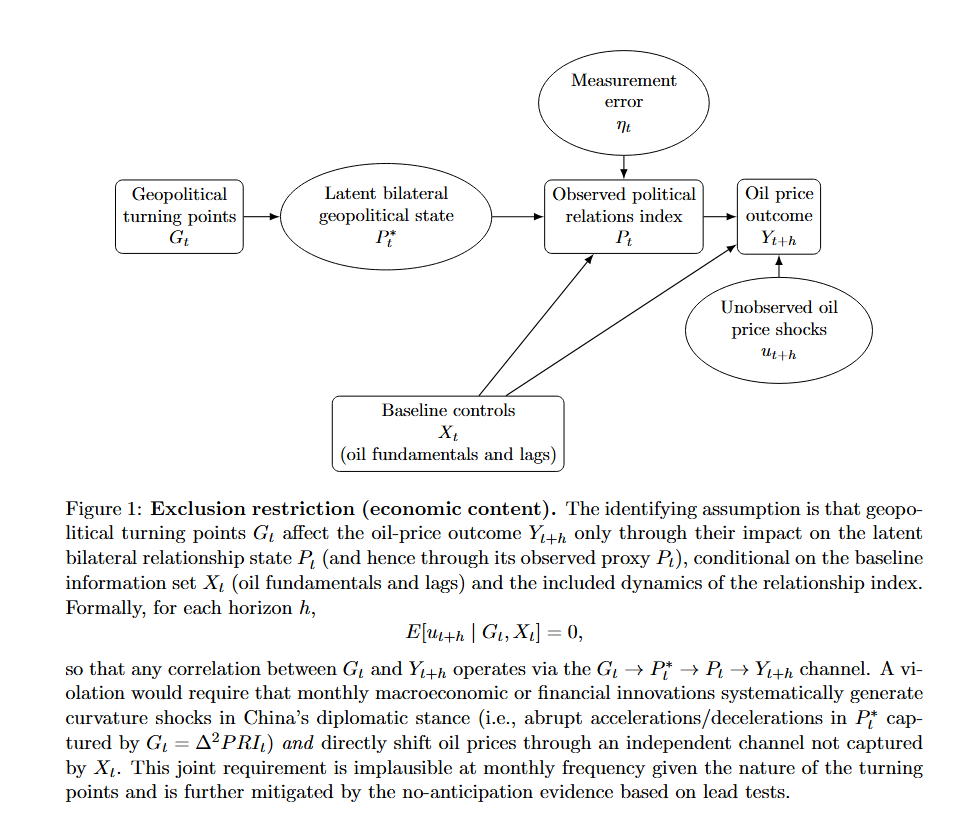

The exclusion restriction is the core causal assumption: conditional on controls Xt, the turning point affects the outcome only through the relationship state. In the causal graph, it is the absence of a direct link Gt→Yt+h.

A useful way to defend exclusion is to state clearly what a violation would require in this design. It is not enough to say “geopolitics and economics interact.” The relevant counterfactual is much sharper:

A violation would require that monthly macroeconomic or financial innovations systematically generate curvature innovations in China’s diplomatic stance—that is, that routine economic surprises at monthly frequency produce abrupt U-turns or inflection points in geopolitical relations in a way that remains after controlling for oil fundamentals and the dynamics of the relationship index.

Clearly, this is a demanding claim. Even if macro conditions can influence geopolitics in the long run, it is a much stronger proposition that short-horizon economic innovations induce discrete accelerations and decelerations in diplomatic posture. Moreover, the direction of causality would have to run from monthly economic noise to geopolitical curvature systematically, not occasionally. Otherwise, the instrument is not endogenously contaminated in a way that threatens the IV moment condition.

Mechanisms are not violations. A frequent confusion in this literature is to treat “risk premia” or “demand expectations” as separate channels that would invalidate exclusion. In this design, the opposite is true: the latent relationship state Pt* is best understood as an information object that markets use to price future states of the world. When Pt* shifts, markets revise (i) expected global activity and hence expected oil demand, and (ii) the compensation required for geopolitical risk. These are economically meaningful channels, but they are not “extra” channels bypassing the relationship state; they are precisely the way the relationship state is transmitted into prices. Put differently, risk premia and demand expectations are functions of Pt*, not independent shocks. A natural interpretation is that Pt* provides a sufficient summary of the geopolitical conditions relevant for pricing: turning points move Pt*, which shifts the conditional distribution of future demand and the pricing kernel associated with geopolitical risk, and oil prices respond accordingly.

In the oil application, the exclusion argument is even more intuitive: turning points in China’s bilateral stance are not oil-market events, and China is not an oil producer deciding the monthly supply. The plausible economic channels through which relations affect oil—risk premia, precautionary demand, and demand expectations—are not separate “violations”; they are precisely the mechanisms by which the relationship state matters for pricing. In this sense, Pt* can be read as a market-relevant summary of geopolitical conditions that embeds expectations about future economic activity and risk. If the instrument shifts Pt*, it shifts those expectations, and oil responds.

Putting these layers together, exclusion becomes a transparent maintained condition: once we condition on oil fundamentals and the rich dynamics of relations, it is implausible that monthly macro/financial innovations are driving abrupt inflections in China’s diplomatic stance toward its main partner.

5) Why this causal design is portable beyond oil

A major advantage of the turning-point strategy is that it is not outcome-specific. The same causal scheme can be used to study trade, firm-level exports, financial variables, commodity markets, and other macro outcomes. The design remains coherent as long as 2 principles are respected:

- The outcome must plausibly respond to the relationship state Pt* through well-defined mechanisms (risk, demand expectations, trade policy expectations, uncertainty, etc.).

- The same diagnostics should travel with the application: strong first stage, non-anticipation via lead tests, and a clear exclusion defense tailored to the outcome’s likely confounders.

Closing thought

Causal identification in geopolitics is fascinating field. It is about whether the econometrics matches a coherent story about information, timing, and institutional behavior. Turning points—curvature shocks in bilateral relations—offer a disciplined way to do that at monthly frequency: they isolate the moments when the geopolitical trajectory changes, they are difficult to forecast in a systematic way, and they are difficult to rationalize as a mechanical consequence of routine macroeconomic innovations. That combination is what makes the design credible for short-run causal inference on the economic effects of China’s bilateral geopolitical relations.

References

Saadaoui, J. (2025). Geopolitical Turning Points and Macroeconomic Volatility: A Bilateral Identification Strategy. Available at SSRN: 5366829.

Saadaoui, J., Strauss‐Kahn, V., & Creel, J. (2026). How geopolitics influences the exports of Chinese firms (January 25, 2026). Available at SSRN: 6130286.

The title is a reference to a movie that I really liked to watch when I was a kid: