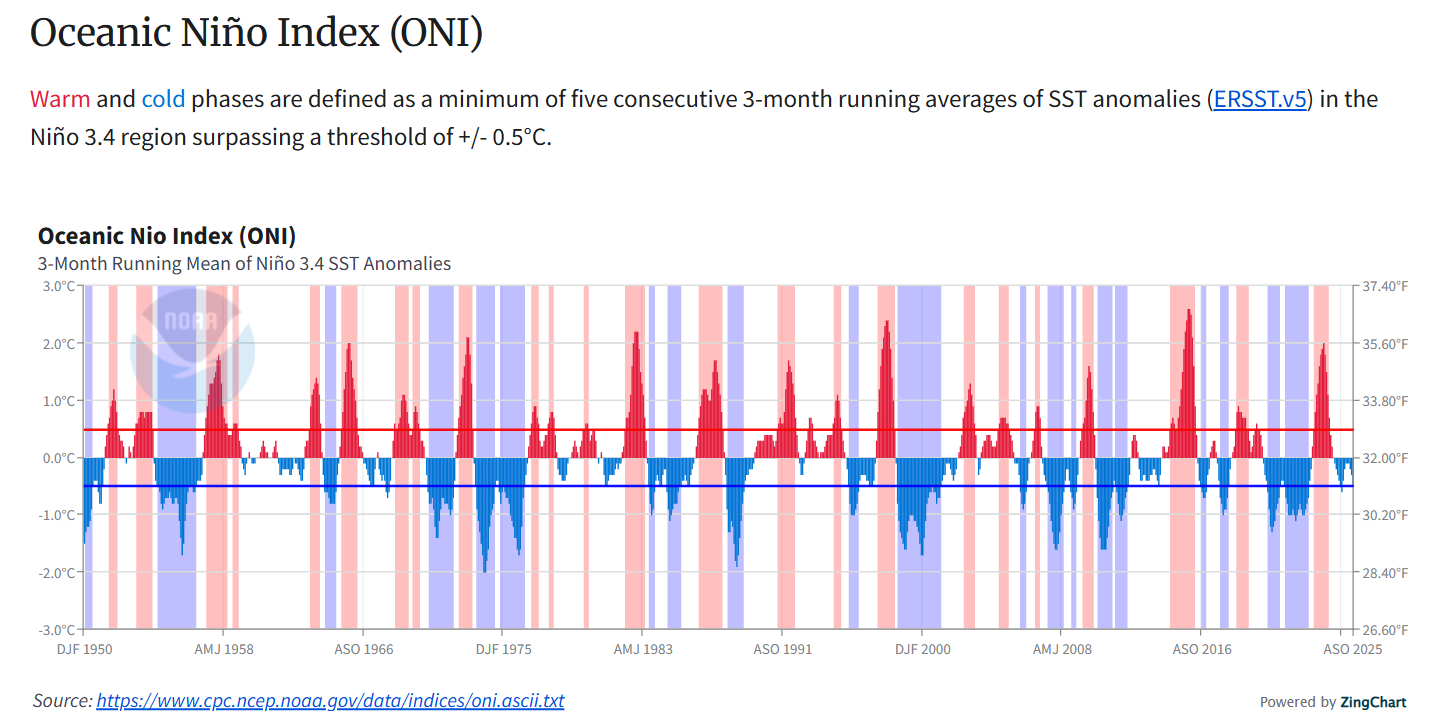

Climate watchers and oil traders are again looking at the same charts. In early autumn 2025, the United States Climate Prediction Center issued a La Niña Advisory. Sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific are now below average, and atmospheric indicators are consistent with La Niña conditions. Current forecasts state that La Niña is present and likely to persist through the 2025 to 2026 winter, with a return to neutral conditions most likely in the first quarter of 2026.

This is a weak event in terms of sea surface temperature anomalies. Nevertheless, past experience shows that even weak La Niña episodes can matter for the oil market, especially when they interact with tight fundamentals, elevated geopolitical risk, and already high climate volatility. In what follows, I summarize the main channels through which La Niña can increase oil prices and relate them to recent empirical evidence, including my joint work on El Niño Southern Oscillation and United States oil spot and futures prices.

Key takeaways

- La Niña is now under way and is expected to persist through the Northern Hemisphere winter of 2025 to 2026. Even if the episode remains weak, historical evidence suggests that La Niña episodes tend to raise energy demand in some large consuming regions and increase the probability of weather-related supply disruptions.

- In our time-varying parameter local projections study for the period 1983 to 2024, El Niño and La Niña shocks do not have symmetric effects on oil prices. El Niño shocks usually reduce oil spot and futures prices, while La Niña shocks, particularly strong or central Pacific episodes, generate persistent upward pressure on prices at horizons within one year.

- The incoming La Niña matters for macroeconomic policy because it can temporarily raise energy and food prices and complicate the distinction between temporary and persistent inflation. For energy importers, it enlarges the upper tail of the oil price distribution during the coming winter, which is relevant for fiscal planning and for the design of targeted support schemes.

Climate background and why La Niña matters now

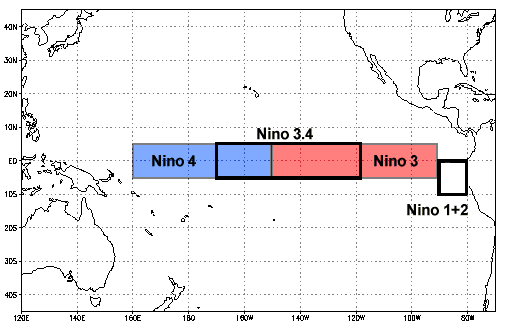

La Niña is the cold phase of the El Niño Southern Oscillation. It is characterized by cooler than normal sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific and relatively warmer waters in the western Pacific. This pattern alters the Walker circulation, shifts rainfall belts, and generates a well-documented set of teleconnections in temperature and precipitation across the globe.

For the 2025 to 2026 winter, the latest forecasts from the World Meteorological Organization and from the International Research Institute at Columbia University indicate a significant probability that La Niña conditions will persist from December 2025 to February 2026, before a likely transition back to neutral conditions during the first quarter of 2026. Most models anticipate a weak or at most moderate event.

Weak La Niña episodes are less likely to generate dramatic regional anomalies on their own, but they still tilt the distribution of weather outcomes. For the oil market, what matters is not only the mean response of weather variables but also the higher probability of certain combinations: colder conditions in parts of North America and northern Asia, more active tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic, and altered rainfall over major agricultural and biofuel regions.

Demand channel: colder weather and fuel substitution

The first channel is the effect of La Niña on energy demand. Typical La Niña winters bring colder and wetter conditions to the northern tier of the United States and to Canada, while the southern tier often experiences warmer and drier conditions. Similar patterns appear in northern Eurasia.

Colder weather in densely populated and energy-intensive regions raises demand for:

- Heating fuels such as natural gas and heating oil

- Electricity for residential and commercial use

- Transport fuels that support logistics and backup generation

Even when the initial shock is concentrated in the natural gas market, oil prices can respond through substitution. During cold winters, high gas prices and physical constraints in gas delivery can lead utilities and industrial users to switch to oil based products where technical constraints allow. This substitution tightens refined product balances and strengthens the link between La Niña-induced heating demand and crude oil prices.

Supply channel: hurricanes, infrastructure and risk premia

The second channel is supply risk. Statistical analysis of past ENSO episodes indicates that La Niña tends to be associated with more frequent and sometimes more intense Atlantic tropical cyclones because vertical wind shear in the main development region is reduced.

The Gulf of Mexico and the surrounding coastal area remain a crucial hub for the global oil system. The region hosts a large share of United States offshore production, a dense network of pipelines, and a cluster of refineries and export terminals. Major hurricanes can therefore:

- Shut offshore platforms and reduce crude production

- Damage or temporarily close refineries

- Disrupt transport and export infrastructure

Even if the physical loss of output over the year is modest, the temporary reduction in effective supply and the logistical bottlenecks can generate sharp price spikes. Markets react not only to realized damage but also to anticipated risk. Once forecasters indicate a La Niña-related increase in hurricane probabilities, traders adjust risk premia in oil futures and options. In practice, this means that La Niña can support higher oil prices even in the absence of major landfall events, simply through higher compensation for bearing supply risk.

Agriculture, biofuels and indirect pressures on oil

La Niña also affects agricultural production. Teleconnection patterns show that La Niña episodes are frequently associated with drought in some parts of South America and East Africa and with excess rainfall in other regions. These anomalies influence yields of crops such as corn and oilseeds that are important inputs into biofuel production.

Higher volatility and higher expected prices for these crops translate into more expensive ethanol and biodiesel. Since biofuels are partial substitutes for conventional gasoline and diesel, particularly in blended fuel systems, a tightening of biofuel markets can spill over into higher demand for petroleum-based fuels. This is another route through which La Niña can contribute to upward pressure on oil prices, even though the original shock occurs in the agricultural sector.

Expectations, inflation and financial channels

La Niña is not an unexpected one-day shock. It develops over several months, and modern forecasting systems provide probabilistic guidance with considerable lead time. As a result, La Niña operates as a forward-looking signal for markets and for policymakers.

Once the probability of La Niña increases beyond a certain threshold, energy analysts and macroeconomists revise expectations about future heating demand, hurricane exposure, and agricultural price volatility. These revisions are incorporated into projections for headline and core inflation. Recent work on ENSO-augmented Phillips curves and on climate-related shocks to inflation emphasizes that La Niña phases tend to contribute to temporary increases in food and energy prices.

In financial terms, La Niña raises not only the expected level but also the variance of energy and food price fundamentals. Higher uncertainty supports higher risk premia in oil futures and options, wider trading ranges, and greater demand for hedging instruments by producers and consumers. Even if realized weather outcomes turn out to be benign, this anticipatory behavior can keep oil prices above the level that would prevail in the absence of La Niña.

Evidence from ENSO and oil prices

In Gallegati, Ginn, Saadaoui, Solomou and Tian (2025), we study the effect of ENSO shocks on United States oil spot and futures prices using a time-varying parameter local projections framework and monthly data from 1983 to 2024.

Three results are particularly relevant for the current La Niña episode.

First, ENSO shocks have statistically and economically significant effects on oil prices even after controlling for standard global macroeconomic variables and for other sources of commodity price variation. This confirms that ENSO is a distinct driver of oil price dynamics, not merely a proxy for global demand.

Second, the effects are strongly asymmetric. El Niño shocks usually reduce oil prices, while La Niña shocks, especially more intense or central Pacific events, generate persistent upward pressure on both spot and futures prices. The responses to La Niña shocks are largest at horizons within the first twelve months, which corresponds closely to the period over which weather anomalies, hurricane seasons and agricultural cycles transmit into energy markets.

Third, the strength of these effects is time-varying. The response of oil prices to La Niña shocks is larger in periods when heating fuel demand is more weather sensitive, when the Gulf of Mexico plays a relatively larger role in refining and exports, and when global food and biofuel markets are tight. In other words, the same physical ENSO shock can have different macro financial consequences depending on the structural configuration of the energy and commodity system.

These findings suggest that the current La Niña episode, even if weak, should not be dismissed. The macro financial environment of late 2025 combines elevated climate volatility, geopolitical tensions, and still high levels of headline inflation in many economies. Under such conditions, the channels described above can more easily translate physical climate anomalies into noticeable oil price movements.

Conclusion

La Niña is now present and is expected to persist through the Northern Hemisphere winter of 2025 to 2026 before conditions likely return to neutral in early 2026. Historical evidence and recent econometric work show that La Niña episodes can place upward pressure on oil prices through four main mechanisms: higher heating and power demand in key consuming regions, higher probability of weather related supply disruptions, shocks to agricultural and biofuel markets, and shifts in expectations and risk premia.

None of this implies that oil prices must rise dramatically in every La Niña episode. ENSO is only one among many drivers of oil markets, and its realized impact depends on the state of inventories, spare capacity, geopolitical events, and macroeconomic policy. However, ignoring La Niña would mean ignoring a recurrent and partially predictable source of variation in the distribution of oil price outcomes.

For policymakers, the incoming La Niña underscores the importance of integrating climate indicators into inflation forecasts, fiscal stress tests, and energy security planning. For firms and financial institutions, it reinforces the case for climate informed risk management and hedging strategies. For researchers, it offers another opportunity to use a quasi exogenous climate disturbance to learn about the sensitivity of the global energy system to physical shocks.

References

Climate Prediction Center (2025). ENSO Diagnostic Discussion, October Update. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/enso_advisory/ensodisc.shtml

EcoFlow (2025). ENSO and Climate Pattern Outlook for Winter 2025 to 2026. EcoFlow Blog. EcoFlow.

Gallegati, M., Ginn, W., Saadaoui, J., Solomou, S., Tian, K. (2025). Not All Climate Shocks Are Alike: How ENSO Impacts Oil Prices. Working paper, September 2025. Available at SSRN 5549860.

International Research Institute for Climate and Society (2025). ENSO Forecast, October 2025. Columbia University, iri.columbia.edu.

World Meteorological Organization (2025). La Niña May Return but Temperatures Are Likely to Be Above Average. WMO Press Release, September 2025, World Meteorological Organization.