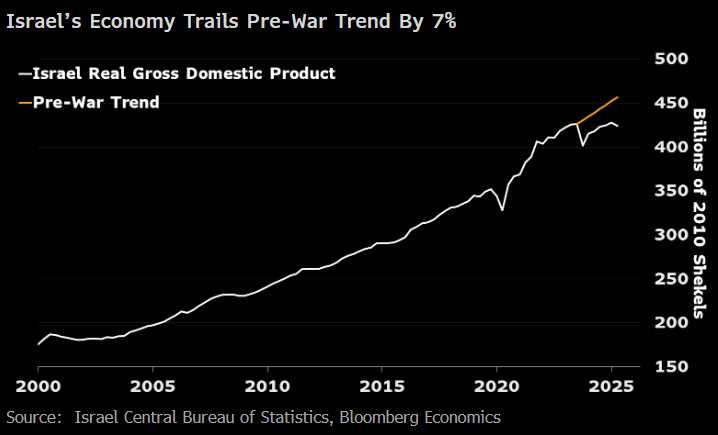

Israel’s economy is now 7% below its pre-war trend. Unlike the COVID-19 recession, this time there is no quick rebound. The plucking model fails under conflict, where instability reshapes the growth path. Together with Joshua Aizenman, Hiro Ito, Donghyun Park , and Gazi Salah Uddin, we explain why in a recent NBER working paper: Global Shocks, Institutional Development, and Trade Restrictions: What Can We Learn from Crises and Recoveries Between 1990 and 2022?

Key Takeaways

- The plucking model worked well for describing the Israeli economy during the COVID-19 pandemic: output fell but quickly rebounded to trend.

- In contrast, the current conflict-driven recession has created a permanent deviation from trend.

- Political instability affects not just short-term demand but also long-term supply, investment, and productivity.

- Wars and conflict shocks are structural, not cyclical—hence the failure of the plucking model.

- The lesson: resilience depends on institutions and stability. Without them, economies do not simply bounce back.

The chart shows that Israel’s real GDP remains about 7% below its pre-war trend. This is unusual if we compare it to the recovery pattern after the COVID-19 recession. Then, output returned to trend relatively quickly, consistent with what Milton Friedman once described as the “plucking model” of business cycles: economies are “plucked” downward by shocks but bounce back to their potential path once the disturbance subsides.

But here, the plucking model does not apply. Why? Because the nature of the shock is fundamentally different.

After the pandemic, the recession was primarily an exogenous but temporary disruption. Once restrictions were lifted, pent-up demand and expansive fiscal-monetary policies drove the rebound. Political institutions remained intact, and households and firms could plan with confidence that the rules of the game had not changed.

By contrast, the current deviation from trend reflects conflict and persistent political instability. Wars and prolonged insecurity are not just temporary plucks—they alter investment decisions, labor participation, capital flows, and expectations in ways that can durably depress potential output. The data show that instead of a rapid rebound, Israel’s GDP path has shifted downward.

This aligns with the insights of a recent NBER working paper (NBER w33757), which revisits the plucking model in the modern context. While the model explains cyclical dynamics in many advanced economies, its predictions break down when institutional or political risks dominate. Structural rather than cyclical forces take the lead.

In Israel’s case, the gap relative to the pre-war trend is not merely a cyclical deviation. It represents a deeper scar on the economy’s long-term growth path.

Conclusion

The Israeli case highlights the limits of the plucking model. Economic rebounds depend not only on the size of the initial shock but also on the stability of the institutional and political environment. After the pandemic, Israel quickly returned to trend because the disruption was temporary and policies were credible. In contrast, conflict introduces persistent uncertainty that undermines investment, labor markets, and productivity, leaving lasting scars. The key lesson is clear: without political stability, economies cannot simply be “plucked” back to their pre-shock trajectory.

References

Aizenman, J., Ito, H., Park, D., Saadaoui, J, & Uddin, G. S. (2025). Global Shocks, Institutional Development, and Trade Restrictions: What Can We Learn from Crises and Recoveries Between 1990 and 2022? (No w33757). National Bureau of Economic Research.