What is science? Science is above all a method aimed at discovering the truth. In a previous post of mine, I recommended a YouTube video capturing a lesson by Richard Feynman recalling the essence of the scientific method: Guess → Compute the consequences → Compare with observation / with experiment → Conclude whether it works.

“If it disagrees with experiment, it is wrong. This simple statement is essential to science. It does not make any difference how beautiful the guess is. It does not make any difference how smart you are. If it disagrees with experiment, it is wrong. Simply.“

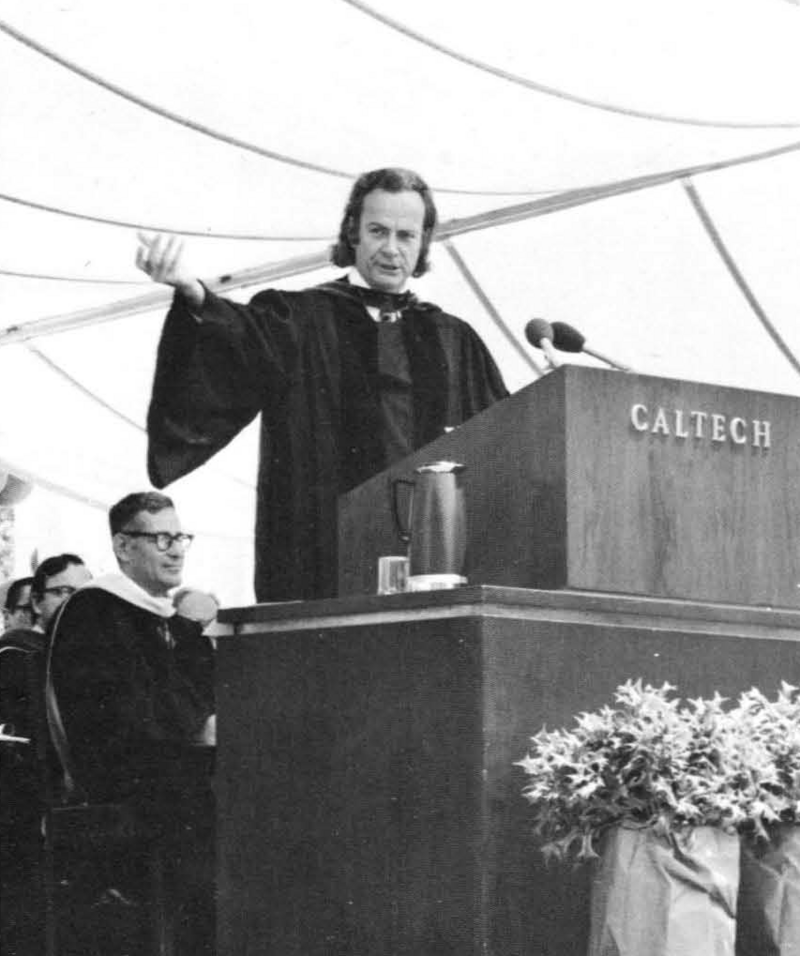

Now let us dive into a talk given by Richard Feynman at Caltech in 1974. Special thanks go to Fermat’s Library for sharing this. The talk is about Cargo Cult Science. Cargo Cult Science refers to the fact that a research can fool itself by discarding the evidence that comforts his/her testable hypotheses. Cargo Cults have really existed, see here. In the following, I quote in italics some abstracts from Feynman’s talk.

“We’ve learned from experience that the truth will out. Other experimenters will repeat your experiment and find out whether you were wrong or right. Nature’s phenomena will agree or they’ll disagree with your theory. And, although you may gain some temporary fame and excitement, you will not gain a good reputation as a scientist if you haven’t tried to be very careful in this kind of work. And it’s this type of integrity, this kind of care not to fool yourself, that is missing to a large extent in much of the research in Cargo Cult Science.”

The place of replication by the scientific community is essential for discovering the truth. We can mention that the replication process by the scientific community is a major concern both in natural sciences and in social sciences, as underlined by John List, here for economics.

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool. So you have to be very careful about that. After you’ve not fooled yourself, it’s easy not to fool other scientists. You just have to be honest in a conventional way after that.“

Confirmation biases are amongst one of the biggest problems for the researcher. So, we need to keep in this mind. We need to control for as much as possible for confounding factors.

“Other kinds of errors are more characteristic of poor science. When I was at Cornell. I often talked to the people in the psychology department. One of the students told me she wanted to do an experiment that went something like this—I don’t remember it in detail, but it had been found by others that under certain circumstances, X, rats did something, A. She was curious as to whether, if she changed the circumstances to Y, they would still do, A. So her proposal was to do the experiment under circumstances Y and see if they still did A.

I explained to her that it was necessary first to repeat in her laboratory the experiment of the other person—to do it under condition X to see if she could also get result A—and then change to Y and see if A changed. Then she would know that the real difference was the thing she thought she had under control.

She was very delighted with this new idea, and went to her professor. And his reply was, no, you cannot do that, because the experiment has already been done and you would be wasting time. This was in about 1935 or so, and it seems to have been the general policy then to not try to repeat psychological experiments, but only to change the conditions and see what happens.“

In this example, the lack of curiosity to replicate previous results may be a fatal flaw, especially in social sciences where the causal relationships are time-varying, and much more fragile than in natural sciences.

“Another example is the ESP experiments of Mr. Rhine, and other people. As various people have made criticisms—and they themselves have made criticisms of their own experiments—they improve the techniques so that the effects are smaller, and smaller, and smaller until they gradually disappear. All the parapsychologists are looking for some experiment that can be repeated—that you can do again and get the same effect—statistically, even. They run a million rats—no, it’s people this time—they do a lot of things and get a certain statistical effect. Next time they try it they don’t get it any more. And now you find a man saying that it is an irrelevant demand to expect a repeatable experiment. This is science?“

No, it is not.

“This man also speaks about a new institution, in a talk in which he was resigning as Director of the Institute of Parapsychology. And, in telling people what to do next, he says that one of the things they have to do is be sure they only train students who have shown their ability to get PSI results to an acceptable extent—not to waste their time on those ambitious and interested students who get only chance results. It is very dangerous to have such a policy in teaching—to teach students only how to get certain results, rather than how to do an experiment with scientific integrity.“

We should be careful to this in economics, too.

“So I wish to you—I have no more time, so I have just one wish for you—the good luck to be somewhere where you are free to maintain the kind of integrity I have described, and where you do not feel forced by a need to maintain your position in the organization, or financial support, or so on, to lose your integrity. May you have that freedom. May I also give you one last bit of advice: Never say that you’ll give a talk unless you know clearly what you’re going to talk about and more or less what you’re going to say.“

I amazed about how this advice on scientific integrity sounds today…