On October 26, 1985, in Back to the Future Part II, Dr. Emmett Brown (Doc) and Marty Mac Fly go back to 1955 after trying to prevent Marty’s son from being arrested in 2015 for an attempted robbery with an heir of Biff Tannen (his grandson, in fact)… Recently, I found in the new Econ 101 textbook by John Komlos a footnote where the Phillips curve was attributed to Irving Fisher in an article of 1926. This instantaneously reminds me of the second episode of Doc and Marty’s adventure… And I had to admit that, indeed, the Phillips curve has been discovered by Irving Fisher long before William Phillips (32 years before, in fact). Thus, unless time travels are possible not only theoretically, the Phillips curve should rather be called the Fisher curve…

I reproduce hereafter the abstract of the seminal contribution made by Fisher in his article of 1926. Indeed, nowadays, there are many interrogations about the true nature of this relationship. Some observers argue that the functional form of this relationship is more complex than we believed. In any case, it seems at least slightly intriguing to read again Phillips’ contribution with the seminal contribution of Fisher in mind…

I Discovered the Phillips Curve

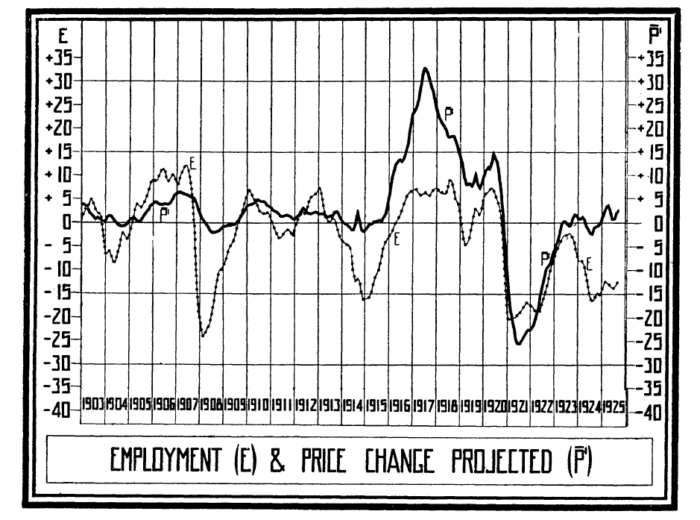

The possible relation between changes in the price level and changes in the volume of employment, much discussed by economists at the present time, has already been debated in the pages of the Review. In the present article Professor Fisher, one of the foremost authorities on monetary problems and for years a protagonist of stabilisation, removes the question from the sphere of controversy to that of exact statistical research. He has found a remarkably high correlation between the rate of price changes and employment, and he describes the methods by which he has achieved this result. The data used refer exclusively to the United States, and further research would be required before the conclusions could be applied directly to other countries. Nevertheless, this objective statistical confirmation of a relation long asserted to exist is a highly important step in advance.

But as the economic analysis already cited certainly indicates a causal relationship between inflation and employment or deflation and unemployment, it seems reasonable to conclude that what the charts show is largely, if not mostly, a genuine and straightforward causal relationship; that the ups and downs of employment are the effects, in large measure, of the rises and falls of prices, due in turn to the inflation and deflation of money and credit.

Irving Fisher (1926).

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1830534

Leave a Reply